Medicare’s challenges have been building for many years. Almost from its beginnings, universal health care in Canada has been under some type of threat. From either dire economic predictions or an onslaught from powerful interest groups, medicare has had to fend off its demise. Related services such as workers’ compensation care, armed forces care, and now virtual care add influential forces on Medicare.

A Short History

In the 1940s and 50s, three western provinces introduced provincial hospital care insurance plans. The federal government followed in 1957 by introducing the Hospital Insurance and Diagnostics Act which provided hospitals, through their provincial governments, with funding to cover the hospital costs incurred by citizens in hospitals – but not doctor’s fees. Then in 1966, and following a Royal Commission on Health Services, the federal government passed the Medical Care Act which funded provinces to cover physicians’ services. With these two federal acts addressing both hospital insurance as well as physician insurance Canadians had “Universal Health Insurance” or Medicare. It is notable that “home care”, while lauded in the Royal Commission on Health Services, was left out of the medicare equation.

Dire Forecasts

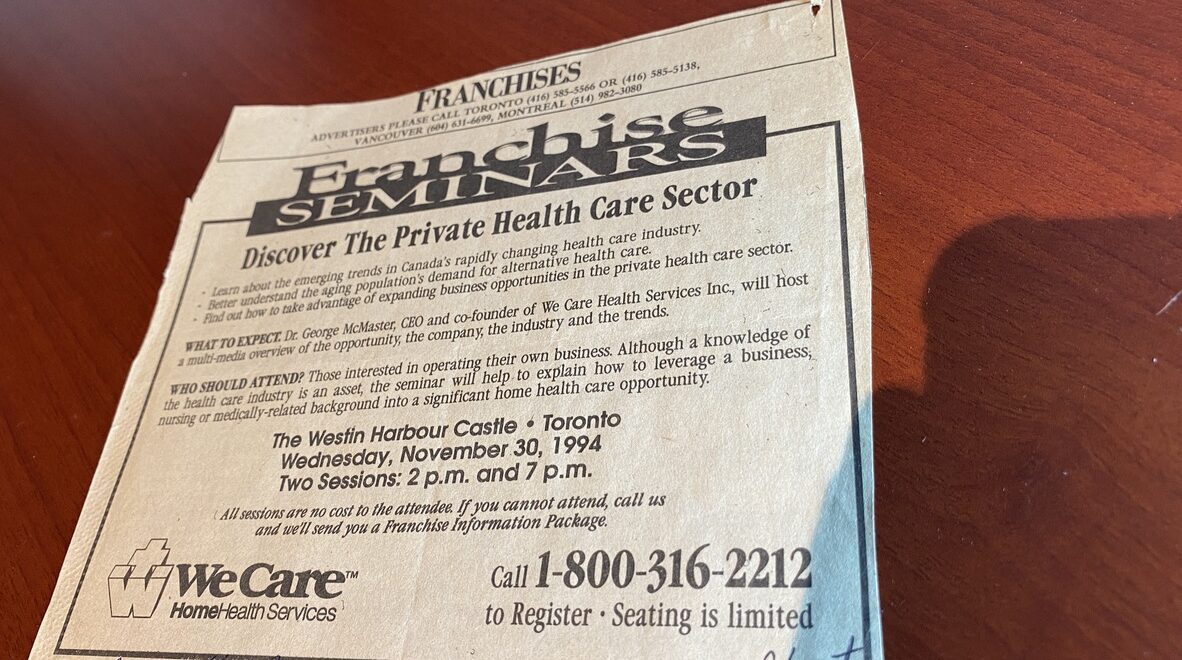

Dire forecasts for Medicare came early. In the late 1960s the Economic Council of Canada predicted that by the year 2000, Canada’s entire GNP would be devoted to covering our universal health insurance program. By the 1980s hospital cost containment rose to the top of provincial agendas. And by the 1990s provincial governments started offloading “out-patient services” such as laboratory testing, diagnostics services, and rehabilitation therapies to companies outside of the hospital. Franchise advertisements started appearing in the Globe and Mail hailing “Discover The Private Health Care Sector”. Large 21st century federal transfer infusions temporarily plugged a few holes but provincial governments continued awarding private for-profit contracts further fragmenting an integrated model of care. Meanwhile, in Ontario, community-driven homecare services, which had originated in volunteer agencies and public health units, were trying to survive on leftovers. Today homecare is being fed a daily budget of 1/4 the per diem funding rate that long-term care homes receive and 1/20th the per diem rate that hospitals receive.

Impending Collapse?

Of Canada’s current population 57% had not yet been born when medicare was introduced in 1967. That is, they weren’t around to experience the hardships of pre-medicare Canada or to witness the political struggle that it took to introduce this nation-building program. Many citizens now simply take for granted our universal health insurance. But while they may be oblivious to the workings of the Ministry of Health, the Ontario Health Insurance Program (OHIP), Ontario Health Teams and the other stewards of our health system, citizens darn well know something is wrong. And they are scared.

Our provincial government seems to be taking the “default” position of backing into a for-profit model of health care. But where has that led? Closures of emergency departments, long wait times for surgery, extra fees tagged onto procedures, 3 million Ontarians without a physician/practitioner, minuscule homecare funding, etc. I thought we discarded that model in 1966. People are looking for help. Which leads me to Medicare Part 3 in the next issue.